Explainable Inference on Sequential Data via Memory-Tracking

04 Oct 2020 - Biagio La Rosa

This post describes the proposed approach of our IJCAI paper “Explainable Inference on Sequential Data via Memory-Tracking” written by Biagio La Rosa, Roberto Capobianco and Daniele Nardi. For further information and results, please check the full paper. You can find also the code here.

Introduction

In the last decade, AI reached a great success thanks to the explosion of Deep Learning techniques. Unfortunately, improvements in performance come at the cost of the interpretability: the high complexity of the networks make them seen as black boxes, where you feed your data into the network and get the output without the possibility to check or to understand the motivations behind that decision.

The eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) field aims to address this problem providing methods that extract insights from the inner working of these systems. While there is an extensive literature on image classification tasks, tabular data and classical settings, there are few works that address the problem on sequential tasks or advanced settings of the latest architectures.

Moreover, most of the model-agnostic approaches start from the assumption that features are independent, or they purposely ignore their dependencies, due to the high computational cost required to compute high order relations between features. Conversely, the most recent architectures like recurrent memory networks, transformers and graph neural networks exploit selective features interaction more and more, creating a gap on the understanding about the motivation behind the success of these architectures. Our work makes a step towards this direction, proposing a method to get explanations about predictions of Memory Augmented Neural Networks on tasks that involve sequential data.

An Example

Let’s begin with an example of a popular model-agnostic method: LIME[1]. This example will show us some of the limitations of these approaches.

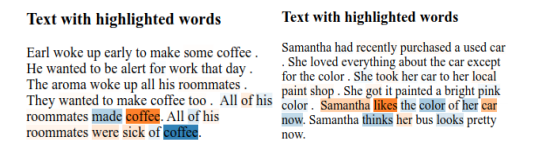

Consider the Story Cloze Test dataset [3], a commonsense reasoning framework for evaluating story understanding. In this task, an agent has to choose between two possible endings for a set of stories composed by four premises each. We trained a Memory Augmented Neural Network, namely a Simplified Differentiable Neural Computer (based on [2]), to solve the problem and then we run LIME on its predictions. An output example is shown on figure 1.

Fig.1: Example output of LIME, where each word in the sentence is weighted based on its relevance. Blue words, if removed, decrease the probability of choosing the first ending; orange words, if removed, decrease the probability of choosing the second ending.

From the figure we can see some of its weaknesses. First of all, model-agnostic methods usually require the input as a whole and it is difficult differentiate between its content, despite the fact that the network could handle some parts in different ways. As a result, LIME focuses the attention on words of the possible endings, telling us how we have to change the words in them to obtain a different result: a scarce information! Ideally, in this case, what we want to know is how we have to change the premises to obtain a different ending, or which premises are more important to obtain the current predicted ending!

The second problem is that it focuses on single words, despite the fact that the under-the-hood neural network is recurrent, and you have not a simple way to extract information at sentence level. Indeed, for each step, a recurrent neural network outputs a state that depends not only on the current step but also on information stored during the past ones. An idea could be sum up the importance of each word in a given premise and extract the premise importance but, as we have seen before, the methods focuses on the endings and the weights associated to the words in the premise are very low, making the premise ranking unreliable.

Our Approach

Our proposal is to exploit the memory, and in particular the reading and writing operations, to build an intrinsic method for Memory Augmented Neural Networks.

Let’s start considering the structure of the proposed Simplified Differentiable Neural Computer.

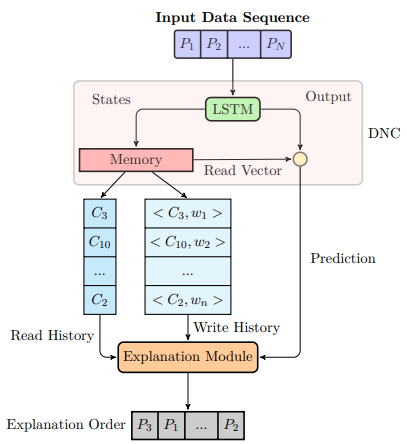

Fig.2: Sketch of the system architecture. From the memory, the read and write history are fed to the explanation module. Specifically, < Ci, wj > indicates that word wj is stored in cell Ci. The output of the explanation module is a vector (at the bottom of the figure), containing a list of explanations sorted by their relevance.

It includes: an LSTM that acts as controller, a memory module and an explanation module. As shown on Figure 2, for each step:

- the controller takes the sequential input and, because it is an LSTM, produces a state on the basis of the current step and the context vector that summarize the previous steps;

- the memory takes the current controller state and performs a read and writing operation. The write operation simply writes into the memory the content of the state. The reading operation uses a content-attention mechanism to retrieve the content of memory cells similar to the current state. The weighted sum of the reading operation is summarized in a read vector;

- the explanation module keeps track of the writing and reading opreation, storing the weights associated to each cells in both of them and storing where the information are written or read during the input parsing;

- At the end, a final layer takes the read vector and the current controller state and returns the final answer.

Hence, the memory content is actively used during the inference process thanks to the read vector. Additionally, to enforce the network to rely on memory, we insert a dropout layer [4] between the controller and the final layer to penalize a little bit its weight in the last layer.

At this point the explanation module has all the ingredients it needs. Based on the given task, it can extract insights from the inner working of the network. For example, in Story Cloze test, it stores all the written cells during the premises parsing and links each word to a subset of cells. Then it considers all the read cells during the parsing of the chosen ending and checks to which word these are linked. Note that we consider only the topX of the read cells for each step.

Let’s consider a simplified example. Suppose that we have an input of the form:

P1: X1 X2 X3

P2: X4 X5

P3: X6

P4: X7 X8

where Pi is the premise i and Xi is a word of that premise.

Suppose that each Xi is stored in a cell called Ci.

During the parsing of your predicted ending, the read history is (or to better say the most read cells are): C2,C3, C5, C1, C5, C7.

Therefore, the explanation module concludes that the networks read 3 times the words of P1,2 times a word of P2 and one time P4. Therefore it assigns a rank of importance to the premises, based on the number of readings. In this case the rank will be P1,P2,P4,P3.

Results

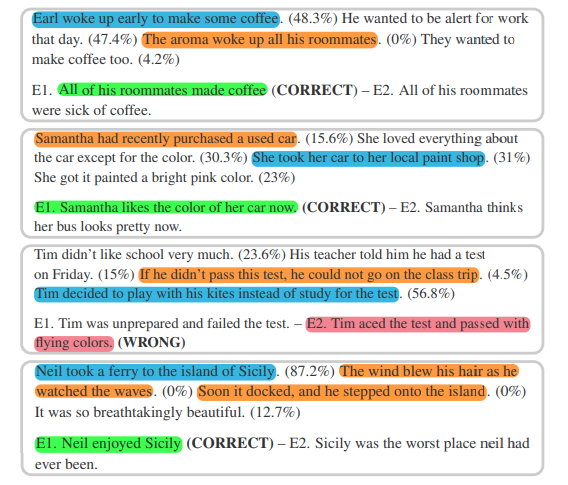

We validate our approach both on a modified version of T-maze and on the Story Cloze Test, but here we will show some results of only the second case. For further results, and a deeper insight about our method, please refer to the paper. Below you can see an output example of our method, where each premise is linked to the percentage of readings during the parsing of the chosen ending.

Fig.3: Example outputs on the Story Cloze Test. A relevance score is associated to each premise — ranked from best (blue) to worst (orange). Predictions are highlighted in green if correct, or red if wrong.

As mentioned before, our method generates a rank. From the rank, we can identify the best and the worst premise, as the premise with the highest and the lowest number of readings. We are interested to check:

- that the rank is enough good;

- how the number of read cells considered for each step (topX paramenter) influences the explanations.

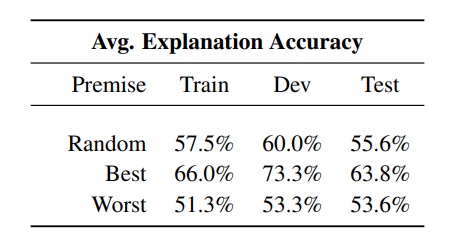

Fig.4: Avg. explanation accuracy over 10 runs on the Story Cloze Test when feeding the model with only a random, the best and the worst premise.

For the first question, supposing that a good explanation is sufficient to

justify a certain prediction, we compute the accuracy of the

model in reproducing its predictions using only the best

and worst premises — in place of the full story. Intuitively,

if the explanation for a certain prediction is good, feeding

that information alone to the network should result often in the

same prediction.

The results are presented in Figure 4. Here the best accuracy refers to the number of times over the total that the prediction obtained using only the best premise matches the prediction obtained using the full story. The worst accuracy conversely refer to the prediction gained using only the worst premise. Ideally, we want a best premise high as much as possible, while the worst premise behavior depends by the specific tasks, but in general should be lower than the best premise accuracy. The best premise extracted by our method outperforms the worst premise and a random selection of premise in all the datasets considered, confirming our hypothesis.

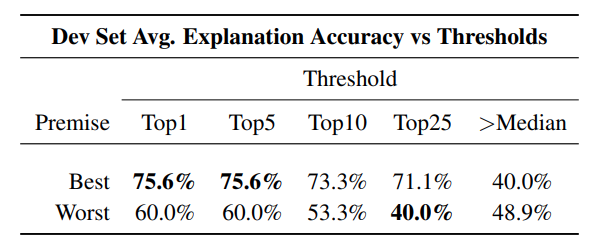

Fig. 5: Avg. explanation accuracy on the dev set over 10 runs for the best and worst premises using different numbers of read cells for each step.

Regarding the second question, we performed some experiments varying the size in the range {1,5,10,25}, reported in figure 5. If topx is 1, it means that for each step we consider as “read cell” only the cell that has the highest reading weight. If topX is 5 we consider the cells with the top 5 highest reading weights and so on.

We find that the best premise improves its performance when we consider few read cells for each step, and it makes sense because the cells considered are only that with highest weights,

they are highly represented in the read vector returned by the

memory and they have a direct influence on the final prediction.

The worst premise accuracy is more tricky. Indeed, using few cells it is likely that the cells refers to only one or two premises, and the choice of the worst premise becomes nearly random. Conversely, using more cell, all the premises will be represented in the read history and the choice of the worst premise become a little bit more reliable.

Finally, we suggest to check out our code to deepen the topic and to reproduce the results presented above.

In conclusion, these promising results make the proposed approach definitely worth additional investigation. In particular, we aim at further improving the quality of provided explanations, better understanding memory-based explanation mechanisms, and extending the applicability of our approach to different domains in future work.

References

[1]: “Why Should I Trust You?”: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier - Marco Tulio Ribeiro, Sameer Singh, Carlos Guestrin. LINK

[2]: “Hybrid computing using a neural network with dynamic external memory”- Alex Graves, Greg Wayne, Malcolm Reynolds, Tim Harley, Ivo Danihelka, Agnieszka Grabska-Barwińska, Sergio Gómez Colmenarejo, Edward Grefenstette, Tiago Ramalho, John Agapiou, Adrià Puigdomènech Badia, Karl Moritz Hermann, Yori Zwols, Georg Ostrovski, Adam Cain, Helen King, Christopher Summerfield, Phil Blunsom, Koray Kavukcuoglu & Demis Hassabis. LINK

[3]: A corpus and cloze evaluation for deeper understanding of commonsense stories - Nasrin Mostafazadeh, Nathanael Chambers, Xiaodong He, Devi Parikh, Dhruv Batra, Lucy Vanderwende, Pushmeet Kohli, and James Allen. LINK

[4]: Robust and scalable differentiable neural computer for question answering - Jorg Franke, Jan Niehues, and Alex ¨ Waibel. LINK